The Near Impossibility of Moving Up After Welfare

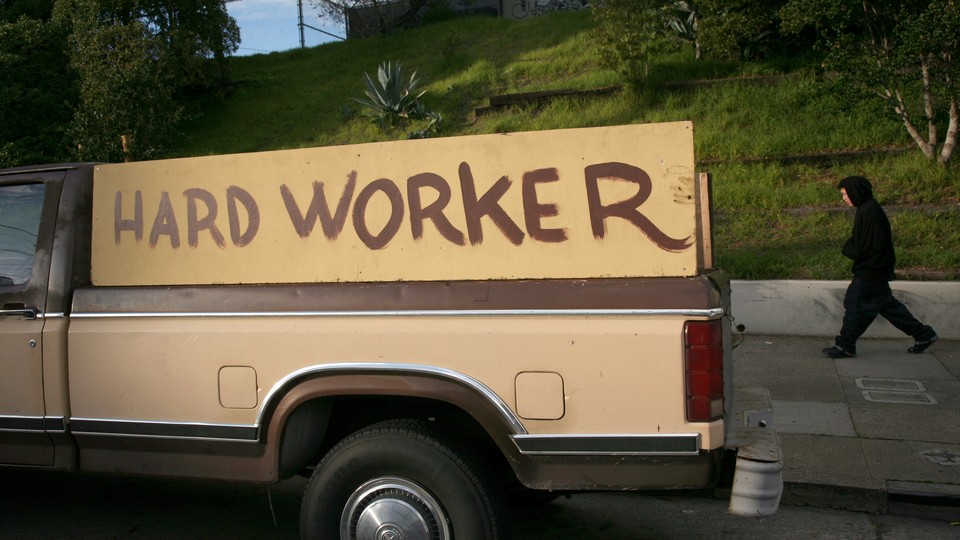

In the wake of welfare reform, unemployed people are pushed to quickly find work, any work. But too often those jobs lead nowhere.

MILWAUKEE—Is it possible for Candace Vance to find a good job?

Vance, 31, is a single mother of two who hasn’t worked for more than a year. She’s on Wisconsin’s version of welfare, called Wisconsin Works, or W-2, which provides her with $650 a month. In order to receive that money, Vance is required to look for a job, and if she doesn’t find one, she’ll eventually lose her benefits.

The challenge, for Vance and for millions of people like her, is that the jobs available to her don’t provide much of a chance to build a better life. Most of the jobs that she is qualified for pay around the minimum wage, which, at $7.25 an hour in Wisconsin, Vance says, is not enough to cover her rent, groceries, and gas, and allow her to have anything left over. Saving up to go back to college is out of the question, and she’s not allowed to go back to school while she’s receiving W-2.

“They say, ‘Go, get a minimum wage job, just to get your butt off W-2, and then you won’t have to depend on us,” she told me. “But we need more than that. You know we need more than that.”

Since Bill Clinton signed welfare reform into law in 1996, work has been billed as the best solution for people like Vance. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, better known as welfare reform, encouraged states to put stringent work requirements on people receiving Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF). In order for states to continue to receive federal money, recipients had to put in a certain number of volunteer or work hours every month, and counselors had to push recipients to take a job, any job, that would get them off the dole. (Each state has its own program to administer TANF; W-2 is Wisconsin's version.)

Wisconsin, which was one of the earliest states to experiment with welfare reform, had some of the harshest work requirements in the country, according to the 1997 account of the state’s reform efforts by Jason DeParle, “Getting Opal Caples to Work,” in The New York Times Magazine. “It is tougher than anything that has come before: virtually no one is exempt,” he wrote.

Reform was successful—in a sense: Today just 3 million people receive cash assistance from the government, down from 13 million in 1995. But reform came at a price. When people could not find jobs in the allowed amount of time, they lost all government help. That thrust them into deep poverty of the type that the safety net would have once prevented. Today, about 1.5 million households, including about three million children, are living on $2.00 per person or less per day, according to the researchers Kathryn Edin and H. Luke Shaefer.

Those who do find jobs are often not much better off than they’d been on the dole. The job market is tough these days for those without more than a high school education. A study of Maryland welfare recipients exiting TANF, for example, found that just 22 percent found stable employment five years after leaving welfare, and for many more the only work available was either temporary or paid poverty wages. There is little hope of moving up. In today’s economy, most people cannot expect to receive the on-the-job training or promotions they might have decades ago. Because wages have stagnated, most people who enter low-wage jobs and stay in them will never see their pay go up significantly. “We used to have more general wage growth in the economy, so you could get a job, hold it, and stay in it,” Pamela Loprest, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, said. “Even if you didn't get more education, you saw some growth in your wages over time.”

Vance, trying to get off W-2, recently applied to a job at Walmart that pays $11 an hour. If she gets it, she’ll start out as a temp and, hopefully, be hired on—if she performs well and if she’s needed. She’d love to go back to school and get trained for something higher-paying, she told me, but the welfare office requires her to find a job, rather than using her benefits to survive while she trains for more fulfilling—and remunerative—work. Without any better options, she’s going to take the Walmart job if it comes through, even though she knows it may keep her stuck in poverty.

“It’s a start,” she told me. “It will certainly help pay the bills, but as far as having a bank account or creating a nest egg, no, it won’t do that.”

The reason Vance is pushed towards work has to do with the complicated nature of welfare reform. TANF money is delivered to states as a block grant, and states can only receive that money if they get a certain percentage of people into the workforce. States now discourage skills acquisition and push people towards finding a job as soon as possible, said LaDonna Pavetti with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “I want to work, but I’m looking for a career, not just a job,” Vance told me.

For many TANF recipients, getting a job doesn’t mean they get off benefits. Wages for people with no more than a high-school diploma are lower than they were a century ago, when adjusted for inflation. The jobs available don’t pay enough to make people self-sufficient, so they turn to the state for food stamps, Medicaid, and even welfare.

Yet there are jobs available for low-skill people, if they can get even just a few weeks of training. Some groups are noticing this and launching programs across the country to help people like Candace Vance move up the career ladder.

The question is whether anything will work.

Mark Kessenich runs one of the most respected places in the country for helping people move up that career ladder. Called Wisconsin Regional Training Program/Big Step (WRTP), it’s considered a sectoral employment program, meaning it solicits feedback from employers about which good-paying jobs they need to fill and prepares people for those jobs. WRTP works with people who have just a high school diploma or equivalent, and trains them for positions that pay well.

“Our goal is to really build training programs that are intended to link people to family-sustaining employment and long-term careers,” he told me.

There are many reasons to think that this program—or one very much like it—would make a huge difference to Candace Vance and other people on welfare struggling to find good jobs, if they were able to attend. That they rarely can is especially unfortunate given that Kessenich’s program prepares people for work in jobs that pay nicely and are in demand.

These are so-called middle-skills jobs, which require education beyond high school but not a four-year degree. That type of work makes up 54 percent of all jobs in the U.S. labor market, according to the National Skills Coalition, an advocacy group seeking to close the skills gap. But only 44 percent of the country’s workers are trained to the middle-skill level. In places like Milwaukee, where many laborers and middle-wage workers are reaching retirement age, there is likely to be even more unmet demand for these type of workers in the future.

Sectoral employment programs, like WRTP, are good at filling this skills gap because they pool together different employers, who can best identify which jobs are in demand, said Kermit Kaleba, the federal policy director for the National Skills Coalition. Training the poor for available, good jobs is a better strategy than pushing them toward a labor market that is currently full of minimum-wage jobs, Kessenich says.

“Taking someone who is struggling and trying to get them a minimum wage job and calling that a success—that might be a benefit for a business, but it's certainly not community development,” he said.

In Milwaukee, the average wage for someone who wants to work but has no skills or higher education is $10 to $12 an hour, Kessenich said. The same person could go through WRTP/Big Step and make from $15.83 an hour to $20 an hour and up in fields like construction or manufacturing. In other programs, participants can train for work as phlebotomists, x-ray technicians, or vocational nurses.

Yet preparing people for these jobs, even if it takes as little as 14 weeks, is considered “long-term training,” and as such, WRTP is not a program that counselors in the welfare office can recommend. If TANF recipients receive months-long training, they aren’t working, and states need to have a certain percent of people working, or risk losing their block grant. What’s more, there aren’t other government programs available to help pay for longer-term training for the very poor. Pell Grants, for example, can only be used for community-college programs that are longer than 600 hours.

Without training or education, it can be nearly impossible for low-wage workers to move up. With it, however, people can do just that.

Shawn Jones, 44, had tried to move up from the low-wage labor market on his own when he walked in the door of WRTP, but hadn’t yet succeeded. He’d been out of steady work for five years, and scraped by cutting grass, painting homes, and installing drywall, sometimes making as little as $150 in a week. He’d had a few periods of homelessness during the worst of the recession, and was frustrated by his own inability to find something stable. Still, when a city employee directed him to WRTP, he was skeptical. “When I came, I thought this was nothing but the same old temporary service trying to help poor black people get jobs for about a week,” he told me.

But Jones started going through training at WRTP, learning how to operate a forklift and what the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) safety requirements were. He learned how to prepare for interviews and how to perform CPR. And then, he applied for and got into a class for people who might be interested in joining the glaziers’ union. (WRTP screens people for certain tailored programs to find those most likely to finish.)

He’s now a union member and is working at a glass factory that is making the panes for a new high rise going up in Milwaukee. He makes $15 an hour. It’s not quite a middle-class wage, but it’s getting closer, he says. He and other WRTP participants “came in off the street, with no qualifications, and all of us were unemployed for at least four or five years,” he said. “Maybe these are the stepping stones we have to take to get to that $20-an-hour position.”

Research suggests WRTP prepares people better than traditional workforce-programs, which are state-run services that attempt to match those without work with the sorts of jobs they are already qualified for—usually very low-paying ones. The group Public/Private Ventures studied the effects of WRTP and two other sectoral employment programs and compared them to more traditional approaches. It found that participants in sector-focused training earned 18 percent more than people in a control group who didn’t get that type of training. They worked more consistently than those in the control group, and were “significantly” more likely to work in jobs with higher wages and that offered benefits.

These are important findings, because they indicate a pathway out of poverty for motivated workers. And it’s a pathway that doesn’t require big student loans or years and years of training. WRTP is free for participants, and classes may just take a month or two. All participants need to do is show up.

“We really work with people who may not be ready to go to work today, but with a little bit of apprenticeship readiness, with a little bit of coaching, could prepare themselves to be good workers,” Kessenich said.

Sectoral training can be incredibly effective in lifting people’s incomes and getting them into careers, not mere jobs. So why hasn’t Candace Vance heard of it?

TANF’s work requirements are certainly part of the reason WRTP sees few welfare recipients. Federal law mandates that at least half of all families receiving TANF in any given state engage in work or work-related activities for an average of 30 hours per week. Programs such as WRTP rarely count as such training, so participants would need to work 30 hours per week in addition to the hours they spent training for a job.

But beyond TANF’s requirements, many policy makers also question whether people like Vance can realistically transition into higher-paying work. About 36 percent of TANF recipients, for example, have less than a high school education. Many struggle with reading comprehension and math skills, yet acquiring basic skills education does not count towards TANF’s work requirements. Many are single parents and have to figure out how to pay for and arrange childcare while they’re going through training. Others don’t have transportation, which can be an obstacle to getting to far-off construction or manufacturing jobs sites. Some don’t have driver’s licenses.

“It’s a good model, it just can’t be the main solution for how to get living-wage jobs for all the unemployed,” Julie Kerksick, a senior advocate at Public Policy Institute, a Wisconsin advocacy and research group, told me, about sectoral employment programs. Kerksick estimates that no more than 5 to 10 percent of the pool of total low-wage unemployed people will be helped by sectoral training programs, because the rest of the people have larger barriers they’re dealing with.

Indeed, many of the participants I talked to at WRTP come from other decent jobs, and in this way, WRTP seemed more like a re-employment service than it did help for people with no experience in the workforce. Shawn Jones, for example, had been an asbestos supervisor, making $14 an hour, for seven years, until the company downsized in the early days of the recession. Another participant, Demicca Coe, had worked as an office administrator until she got laid off—she now works building transformers in a factory and makes over $20 an hour.

But why not help people like Candace Vance with the obstacles she is facing so that she, too, can go through a program like WRTP? What if there were a program that could provide Vance with child-care, health insurance, and a stipend while she got trained at WRTP, rather than just direct her to a minimum wage job? That was the gist of a different program in Milwaukee that is lauded by policy experts nationwide as an example of something that can help stabilize one-time welfare recipients. The New Hope program, which was a demonstration project that ran from 1994 through 1998 in inner-city Milwaukee, provided workers with help finding jobs, an earnings supplement so that they wouldn’t be living in poverty, low-cost health insurance, and subsidized childcare. Eight years after people entered the program, they were more likely to be employed and living above poverty than a control group. They had higher marriage rates and greater mental health stability. Their children performed better in school than the control group. Subsequent studies found that it helped reduce poverty by at least 50 percent. The premise of New Hope, says Kerksick, who helped run it, was that anybody who wanted to work should be able to find a good job that would help them escape poverty.

“It's pretty amazing, when people have the experience of somebody saying, ‘If you want to work, I guarantee you I can help you find a job,’” she said. “It takes away that sense of despair and hopelessness.”

New Hope took one of the tenets of welfare reform—poor people must find jobs—and made sure that people could find these jobs, and that they earned good wages when they did so.

In a way, that’s what sector-based employment programs do, too. They help people who are poor get jobs that pay them something they can make a life out of.

The system that Candace Vance navigates today began to take shape in Wisconsin and across the country more than two decades ago. It was Wisconsin Governor Tommy Thompson who began experimenting with welfare reform even before the national bill was passed. Then, Thompson and other policymakers harnessed a national aversion to giving away money to poor people and asking nothing in return. The poor could get benefits, they said, but only for a certain amount of time. Then they had to work.

What they missed, then and now, is that this work requirement would not be a path out of poverty. Instead, one-time welfare recipients would find jobs at the bottom of the wage scale and be stuck there, often for life. Or they’d face barriers that prevented them from getting a job, and fall off the welfare rolls and into even deeper poverty.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Both WRTP and New Hope have showed that, in Milwaukee and other cities, people can thrive when they are helped to find good jobs that lift them out of poverty, rather than keep them stuck in it. Punitive measures may work for some people, but for the many, opportunity is the best motivation.

If welfare reform emerged from Wisconsin, so, too, did potential solutions for fixing its worst mistakes. Those solutions are premised on the belief that Candace Vance deserves not just a job, but a good one.